Air raid drill memories from under the desk

By Anthony Buccino

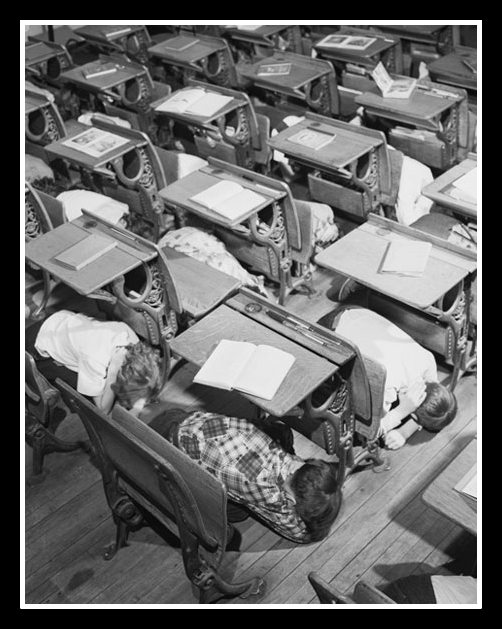

We took cover in neat order in virtually any place that was away from the windows. We sneaked a look back and waited for the Russian’s A-bomb to come crashing through any one of the many windows in our school.

When we heard the school bell ring its special ring - different than a fire drill ring or dismissal bell - we sprang into action from our desks.

Teacher calmly reminded us it was an air raid drill, Form two lines, she barked sternly. We obliged, filing out the doorway.

In the hallways our long neat rows would have shown those Russians. Our lines were the best in the world. We marched proudly in the corridor and filed into the gymnasium.

Quickly and quietly we lined up, then even though we were in our good school clothes, we lowered onto the floor assuming the air raid drill position.

We had our left forearm under our forehead and our right arm over the back of our head with a hand over our ear to muffle the sound of the end of the world.

From the hallway entrance to the gymnasium we must have looked like so many neat rows of Lincoln Logs.

We were lying on the floor as the rest of the school filed in to fill out the gym floor. The older grades lined up against the cold tile walls and metal lockers built into the walls.

We took cover in neat order in virtually any place that was away from the windows. We sneaked a look back and waited for the Russian’s A-bomb to come crashing through any one of the many windows in our school.

Oh, why, we wondered, did they have so many windows in this school building. We could have a much better chance of survival in a nuclear holocaust if only our school had no windows.

Without any windows, wed be way ahead of all the other schools in America. Then we could rule the world after the war, we reasoned.

The littlest of the children did not leave their classrooms at all, they simply took cover under the extensive protection of the wooden surface of their class desks.

All the while we headed for and assumed our position for the air raid, the air raid signal clanked and clanked heightening our sense of emergency.

Air raid drills were rote, as common in those days as fire drills and spelling tests on Wednesday. We took it in stride in the natural order of the day.

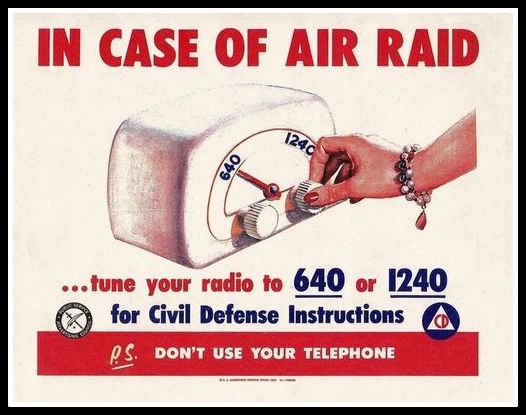

It was the test of the Emergency Broadcast System on our Good Guys radio station or during our afternoon game shows that irked us more.

After all, the TV and radio tests came on our own time. Plus, they interrupted our Top 40 or a favorite show.

At the beginning of the EBS test they told us, “This is a test. This is only a test.” Then the TV screen went to a ‘test’ screen and all we heard from either medium was a boop tone.

In about a minute, it was over. They reminded us This is a test. This is only a test. Had this been a real emergency, you would have been told where to tune for further instructions.

We passed the EBS test. All was well with the world. No emergency, neither hurricane nor Russian bombers, nor Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles were heading our way. It was back to our regularly scheduled program.

What irked us most about being distracted by a test of the EBS was that sometimes they returned us to our show which was “already in progress” so we had to think for another minute to figure out what we might have missed.

In those days the radio dial had a triangle in the number, it was called a Conelrad, that was supposed to be where we would tune in our AM transistor radios and know where to take cover if the Russians decided to attack after we got home from school.

Some of us, and I won’t mention any names, used to leave their homework until the last minute. They figured there was no use in doing homework tonight if the world was going to be over by morning.

Before I started school in the

last year of the 50s

Cold War, the older kids reported being issued

high-heat resistant dog tags with their names and addresses. They had to

wear them at all times.

Before I started school in the

last year of the 50s

Cold War, the older kids reported being issued

high-heat resistant dog tags with their names and addresses. They had to

wear them at all times.

Carried out logically, comedian Robert Klein - a child of the 50s - noted that if you were burned beyond recognition in a nuclear holocaust, they could tell who you were by your name tags.

Whoever ‘they’ would be after World War III, nobody stopped to think about.

By the time I got to school, someone must have figured there was no reason to give my class dog tags, hah, let whoever is left figure out who were all these children turned to dust where the school used to be.

When the clanging bell finished tolling, we got the ‘all clear’ signal. Not until then were we allowed to rise up from the dust on the floor, the dark hallway lockers, or crawl out from under our desks.

We headed back to class and resumed quenching our thirst for knowledge safe in the comfort that if the Russians attacked, at least all the children in my school knew just what to do until the A-bomb came through the window.

First published in Worrall Community Newspapers on August 7, 1997.

Adapted from RAMBLING ROUND Inside and Outside at the Same Time

This is how we rolled ...

ANTHONY'S WORLD

Anthony Buccino

Essays, photography, military history, more

New Jersey author Anthony Buccino's stories of the 1960s, transit coverage and other writings earned four Society of Professional Journalists Excellence in Journalism awards.

Permissions & other snail mail:

PO Box 110252 Nutley NJ 07110

Follow Anthony Buccino

Shop Amazon Most Wished For Items

Web site will receive a stipend for purchases made through Amazon link.

Support this site when you buy through our Amazon link.